Chris Harris on writing The Alphabet’s Alphabet

The crowd was livid at me. Dozens of screaming faces inched closer and closer as I backed against the wall. Only two things stopped me from running for the exit:

The crowd was livid at me. Dozens of screaming faces inched closer and closer as I backed against the wall. Only two things stopped me from running for the exit:

1. The exit was behind them—I’d never make it out alive.

2. They were all second-graders.

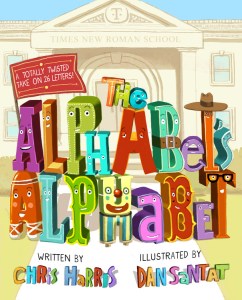

I’d been showing the classroom galleys of my new, Kirkus-starred book, The Alphabet’s Alphabet, out in September. They’d been loving it—until they turned on me.

Like most of the poems in I’m Just No Good at Rhyming, The Alphabet’s Alphabet started with a small moment between me and my kids. When I give school talks (not-so-sub-subtext: invite me to give a school talk!), I always talk about how I write poems:

1. I start with something real—something that made me laugh, or think, or cry.

2. Then I add a what if to it.

That first step is basically the old tip to “write what you know”. On the surface, it’s a weird tip. If we screenwriters really only wrote what we knew, there’d be way fewer films about saving the planet from galactic overlords and way more films about trying to get grape jelly stains out of sweatpants. But of course the point is to start with a memory or observation or feeling that stands out to you. If you felt something, then other people will, too.

For the second step, I use the phrase “what if” instead of “imagination” because once I misspelled “imagination” in front of a group of sixth-graders and never recovered.

Quick example: Once when my daughter was four, I asked her to see if her two-year-old brother was still taking a nap. So she walked quietly down the hall, opened the door to his room, then screamed out, “SILAS, ARE YOU STILL SLEEPING?!” Later on, as I laughed about that moment, I wondered, what ifthere was an otherwise-sweet lullaby that had to be shouted just as loudly as my daughter’s question? That became a favorite, ear-piercing poem in the collection.

If we have time during my school visits, we’ll follow these steps to create a new poem together on the spot. The goal is to get kids excited to write and to help them realize what my own family realized a long time ago: I’m not special. If I can create books using my own life and imagination, then each one of them can, too.

The Alphabet’s Alphabet started when one of my kids pointed out that a Z looks like an N that tripped and fell. From there we traded more jokes about how letters might turn into each other, until I wondered… what if we described every letter using a different letter of the alphabet?” After way too much time making connections on what looked like a conspiracy theorist’s bulletin board, I had it all plotted out. The first couplet: “An A is an H that just won’t stand up right / A B is a D with its belt on too tight…”

And then Dan Santat signed up and made everything far better than I could have ever imagined. I have mixed feelings about Dan Santat. On the one hand, he’s brilliant. On the other hand, the fact that he illustrates thirty zentillion books a year, each one breathtakingly beautiful and unique in its own way (did you see LIFT? you should), makes me feel like dirt about my own productivity.

But I’ll forgive him because of what he did with this book. Every page of The Alphabet’s Alphabet is like a glimpse into a bright, idyllic world of sentient letters that I sometimes wish I lived in instead of this world. I simply wrote, “An F is an A with one leg up for stretching”. Off that, Dan created a gorgeous sun-drenched dance studio, with three As in various stages of putting a “leg” up, so that readers can see the actual transformation from A to F (and with the middle A complaining as it struggles, “This was so much easier when I was lowercase”). My description of a Q as “an O that did not tie its laces” became a full shoestore scene, complete with shoeboxes bearing awesome brand names like “AbcDIDAS” and “ReeBOOK”.

Those second-graders were eating it all up. With each page their eyes got wider as they shouted out connections they noticed among the letters (in fact, that’s the theme of the book: letters are like a giant family; they share resemblances in surprising ways). And then we got to the letter S: “An S is an S. It just is, and that’s that.” (the rest of the couplet: “A T is an I in a fancy new hat.”) Most of the kids laughed, but one of them asked, “Why didn’t you say S is like another letter?”

So then I did what felt natural in that moment: I lied to them. I told them, “Because it’s impossible. There is no way to describe the letter S using another letter.” That’s when they erupted in anger, shouting about how wrong I was. They were simultaneously frightening and adorable—like a room full of Chucky dolls. And they’d fallen right into my trap. “Okay,” I said. “Prove it. What if we wrote our own book describing S using other letters? Who has any ideas?”

And wow, they had ideas. A backwards letter Z, two C’s hanging from a trapeze, an I that’s pretending to be a snake… That electrical fizz-pop of watching the wheels turning in all those heads—combining their own real observations with their own what ifs to make their own creations—that was the goal all along. Within five minutes, we had over twenty ideas—practically a whole new book, entirely about the letter S. Knowing Dan, he’s probably already illustrated it.